Wild West in a Nutshell

COMMENTS? PLEASE LEAVE THEM BELOW.

THIS PAGE PRESENTS AN INTRODUCTION TO THE "WILD WEST," THE COLORFUL 30 YEARS THAT FOLLOWED THE CIVIL WAR — HERE, YOU WILL FIND CONTEXT FOR KEY WILD-WEST PEOPLE AND EVENTS DISCUSSED ON OTHER PAGES.

Old West Firearm

Image Created by Cyberlink's Subscription Power Director 365 AI Image Generator

These are working replicas of 4-4-0 steam locomotives - the originals met at Promontory Summit in Utah, USA on 10 May 1869. The meeting represented the completion of North America's first transcontinental railroad. The ceremony was marked by driving the last four railroad spikes - the 4th-to-last, 3rd-to-last, and 2nd-to-last spikes were made of gold, silver, and a gold-silver-iron alloy. The very last spike was gold. Photo by James St. John. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, and no changes were made to the image.

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Creative Commons License

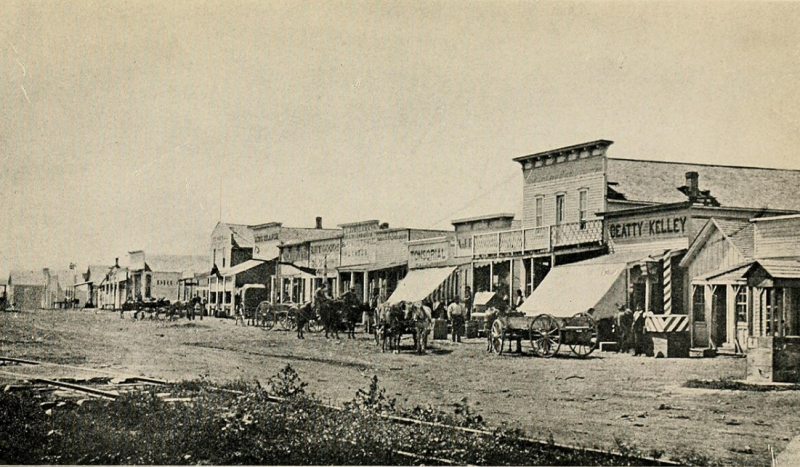

Dodge City, KS, 1878

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Davis Tutt

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

The Cowboy, Painting by Frederic Remington

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Wyatt Earp

Wyatt Earp at age 21 in 1869 or 1870, around the time he was married to his first wife, Urilla Sutherland. Probably taken in Lamar, Missouri.

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Lt. Col. George A. Custer

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

John Wesley Hardin

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

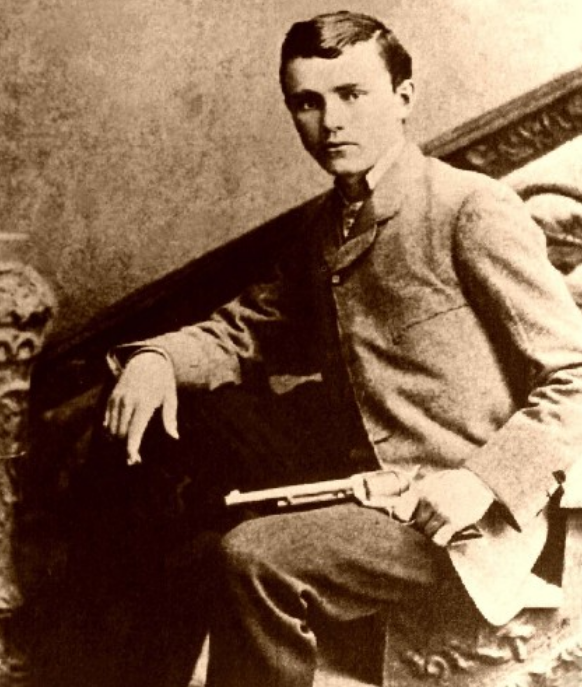

A Young Pat Garrett

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Judge Phantly Roy Bean, Jr.

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Bass Reeves

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

William F. Cody,

a.k.a.

"Buffalo Bill"

Image Via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Julia Bulette

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Ghost Dance Shirt

Photographed in May 2017

by Jim Heaphy

at the

Blackhawk Museum,

Danville, CA

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

John Younger

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

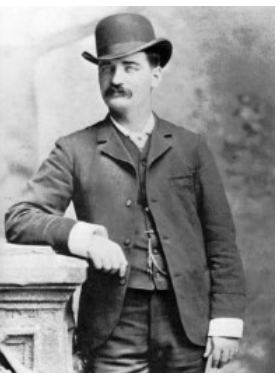

Bat Masterson, 1879

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

The End of a War and the Start of a Wild Era

In 1865, the ink was barely dry on the Civil War’s peace agreements when a new chapter of American history began on the untamed frontier. The era known as the “Wild West” is commonly defined as spanning the three decades after the Civil War, roughly 1865 to 1895. The nation’s Manifest Destiny was in full swing, urging Americans to expand westward “to overspread the continent allotted by Providence” as one newspaperman had proclaimed years earlier. Now, with the war over, thousands of restless young men – former Union and Confederate soldiers alike – drifted west in search of opportunity or escape. They were joined by settlers pursuing free land under 1862's Homestead Act, fortune-seekers chasing new gold and silver strikes, and entrepreneurs riding the expanding railroads into frontier towns.

Several factors sparked the beginning of this wild era. The post-war frontier territories (places like Dakota, Montana, Arizona, New Mexico, and beyond) were vast, under-governed, and often lawless. Boomtowns sprouted overnight near mines and railroad stops, filled with saloons, gambling dens, and brothels to entertain the overwhelmingly male population. The West’s population imbalance (many more men than women) and sparse law enforcement created an environment ripe for violence and vice. By the late 1860s, as the Transcontinental Railroad neared completion, it became easier than ever to travel west, bringing both respectable settlers and outlaws into the frontier. Former Confederate guerrillas, unwilling to return to peaceful farming, sometimes turned to banditry (the infamous Jesse James was one such example, driven to crime after finding peacetime life “no longer enticing”). Meanwhile, the U.S. Army redeployed to fight Plains Indian tribes in a brutal contest for land, setting the stage for legendary battles that would punctuate the era. In short, the Civil War’s end lit the fuse for the Wild West: a perfect storm of adventurous spirit, lack of law, economic opportunity, and lingering gun smoke from the war that just ended.

Lawlessness & Legend On the Frontier

From cow towns in Texas to mining camps in the Black Hills, the late 19th-century western frontier earned its “wild” reputation. Lawlessness was common – or at least, it was perceived to be, thanks to newspaper correspondents and dime novelists who eagerly sensationalized frontier violence. Gunfights, train robberies, barroom brawls, and stagecoach holdups became staples of the Wild West mythos. Yet daily life was often more mundane. Many frontier towns did have sheriffs, judges, and jailhouses, but they were thinly spread. In places like early Dodge City or Deadwood, a quick temper and a six-shooter often settled disputes before the law ever got involved. This was an era when a minor argument over a card game or a poker debt could explode into gunfire at high noon in the town square.

One of the first iconic gunfighters to capture the public’s imagination was Wild Bill Hickok. Hickok had been a Union scout in the war, but in peacetime, he wandered as a gambler and lawman. In July 1865, only a few months after Appomattox, Wild Bill strode out to face a rival, Davis Tutt, in Springfield, Missouri. The two men drew their pistols at a distance and fired – Hickok’s bullet struck true, killing Tutt. This showdown, over a disputed pocket watch and a gambling debt, has been called the first true “Wild West” duel. It instantly elevated Hickok to national fame as the very image of the cool, deadly gunslinger. Such duels were actually rare, but dime novels and newspapers made them seem commonplace. Hickok’s legend only grew: he later wore a marshal’s badge in Kansas and supposedly could shoot a cigar from a man’s lips. In reality, Wild Bill was as mortal as anyone – in 1876, he was shot in the back of the head by a disgruntled drifter while playing poker in Deadwood. Famously, Hickok died holding a pair of aces and eights (plus an unknown fifth card), a combination forever after known as the “Dead Man’s Hand.”

If Wild Bill Hickok embodied the gunslinger myth, the American cowboy became the symbol of the frontier’s freedom. In popular imagination, the cowboy is a rugged hero riding tall in the saddle. The reality was a bit less glamorous. Cowboys were generally hired hands driving herds of cattle hundreds of miles across open range. It was grueling, dusty work – they weren’t even called “cowboys” at the time, but rather cattle herders or drovers. One contemporary noted these men often wore the same outfit until it “turned into rags” and rarely, if ever, took a bath. Many were teenage boys, Mexican vaqueros, or freed slaves trying to make a living in the saddle. They faced rattlesnakes, stampedes, and prairie storms more often than pistol-toting bandits. Still, when those trail-weary cowboys finally reached a rail town like Abilene or Cheyenne with money in their pockets, all that pent-up energy often spilled into wild revelry. Saloons, gambling halls, and brothels did booming business on a cowboy payday, and local sheriffs learned to be either very understanding or very quick on the draw. The legendary lawman Wyatt Earp began his career taming such cow towns – in Wichita and Dodge City, Kansas – where he earned a reputation as someone who could (usually) knock rowdy cowpokes over the head rather than resort to gunplay.

Yet gunplay did erupt at times, fueling the Wild West’s most legendary events. Frontier violence ranged from famous one-on-one duels to full-blown battles involving hundreds. Each time, newspaper reports and later storytellers turned these incidents into American folklore. A perfect example is the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona. The 1881 shootout has been dramatized in countless books and films as the ultimate showdown between righteous lawmen, including Wyatt Earp and his brothers, and the cowboy outlaws of the Clanton-McLaury gang. In truth, the fight was a messy 30-second blast of lead behind a livery stable on Fremont Street – not actually inside the O.K. Corral at all. About 30 shots were fired in half a minute, leaving three of the cowboys dead and Virgil and Morgan Earp wounded. Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday walked away unharmed. The conflict had been brewing over horse thievery and an attempt to enforce Tombstone’s gun control ordinance – ironically, the famous shootout was sparked when the Earps tried to disarm the Cowboys in town. Local testimony was conflicted over who drew first, but the Earps were exonerated in court. What matters for legend is that this dusty skirmish became the Wild West gunfight in the public mind, symbolizing frontier justice. In later years, Wyatt Earp himself helped shape the story, ensuring that he and Doc Holliday would be remembered as larger-than-life figures (though in reality, Earp was a complex man—a sometime lawman, sometime gambler, and opportunist who wasn’t above bending the law). The O.K. Corral shootout lives on as legend, but as one historian quipped, it “lasted only 30 seconds and didn’t take place at the O.K. Corral at all.”

The West’s violence was not limited to shootouts between outlaws and sheriffs – it also encompassed brutal conflicts with and among Native Americans. Perhaps the most dramatic was the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn, often called Custer’s Last Stand. In June of that year, Lt. Colonel George A. Custer led about 210 U.S. cavalrymen into battle against a coalition of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne warriors in Montana territory. The result was a shocking defeat: Custer and every soldier with him were killed in less than an hour. News of the annihilation electrified the nation. To the American public, it was a heroic last stand by Custer; paintings and poems portrayed him gallantly fighting to the end. In truth, the fight was likely a sudden rout – Custer’s troops were vastly outnumbered (some thousands of Native warriors against his two hundred men) and they “never stood a fighting chance.” Nonetheless, Little Bighorn became legend, cementing Custer’s name in frontier lore (even as it spurred the U.S. Army to redouble its efforts, which led to the defeat of the Plains tribes within a few years).

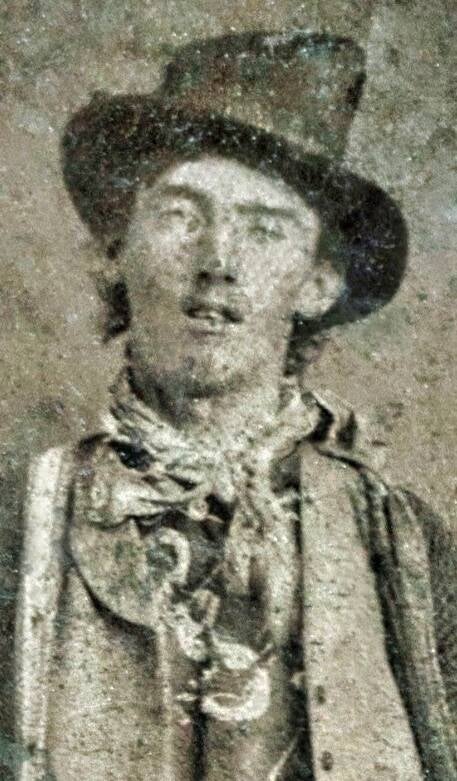

The line between history and myth was often blurry in the Wild West. Take the story of Billy the Kid. William Bonney, alias “Billy the Kid,” was a young outlaw in New Mexico who became famous for his role in the Lincoln County cattle war of 1878. Newspapers dubbed him “The Kid” and attributed all sorts of bloodshed to his name. Billy was rumored to have killed 21 men – “one for every year of my life,” he supposedly bragged. In reality, by more reliable accounts, he likely killed about 8 or 9 people in total. Compared to some of his contemporaries, that wasn’t an extraordinary tally – the deadly Texas gunman John Wesley Hardin probably killed over 40 men in his career. But Billy’s legend loomed larger than his deeds. He had a boyish charm and a flair for the dramatic that storytellers loved. He famously escaped from jail in 1881 by killing two deputies, and then was hunted down and shot in the dark by Sheriff Pat Garrett a few months later. His youth at death (just 21) froze Billy the Kid in time as an almost romantic figure – the reckless boy outlaw with a Colt revolver in each hand and a $500 bounty on his head. Never mind that he was also a cattle rustler and killer; dime novels turned him into a folk hero of the range. Meanwhile, someone like John Wesley Hardin – a far more dangerous man who once shot a stranger for snoring too loudly in the next room – remained less famous in legend, perhaps because Hardin lacked the Kid’s youthful mystique. (Hardin’s story ended in 1895, when he too was gunned down – shot in the back of the head while playing dice in a saloon, karma catching up at last.)

Colorful Characters of the Wild West

What makes the Wild West so enduring is not just the shootouts or robberies, but the colorful characters – both real and legendary – who walked its streets and rode its trails. These characters range from virtuous lawmen to vicious outlaws, and often it’s hard to tell which is which. Many became household names, and their life stories were filled with humor, drama, and tragedy in equal measure.

- Wyatt Earp & Doc Holliday: Wyatt Earp is remembered as the steely-eyed lawman of Dodge City and Tombstone, but he was a multifaceted figure. He chased outlaw cowboys with a vengeance after his brother Morgan was assassinated – leading a deadly vendetta ride – yet Wyatt also spent years as a saloon keeper and gambler, skirting the law himself. His friend Doc Holliday was a tubercular dentist-turned-gambler with a quick wit and an even quicker draw. Holliday’s sardonic humor in the face of death became the stuff of legend (films have him coolly drawling lines like “I’m your huckleberry,” embodying his daredevil spirit). He was deadly when provoked – at the O.K. Corral, Doc’s shotgun blast was said to have felled Tom McLaury – but he was also a tragic figure, coughing blood into his handkerchief, knowing his days were numbered. When Holliday died of tuberculosis in 1887 at age 36, far from the Arizona deserts in a Colorado hotel, his last words were reportedly, “This is funny,” perhaps amused that he died in bed and not with his boots on. Wyatt Earp, by contrast, survived into old age and lived long enough to see himself portrayed as a hero in the early Hollywood Westerns, proving that some legends get to write their own epilogue.

- “Wild Bill” Hickok: As mentioned, Wild Bill’s life was one of high drama and violent action – scout, spy, lawman, professional gambler, and crack shot. He survived countless close scrapes (legend has it he once killed a bear with only a knife) and staged spectacular gunfights like the duel with Davis Tutt. But humor touches even his bloody tale: Hickok was known to spin tall tales about himself, claiming once that he’d let himself be bitten by rattlesnakes just for the entertainment of onlookers. In Deadwood, when his luck finally ran out, the bitter irony of the great gunfighter being shot from behind gave rise to dark humor in saloon songs (one popular verse crooned “the dirty little coward that shot Mr. Howard,” Mr. Howard being the alias Hickok used). Hickok’s death while holding aces and eights – the “Dead Man’s Hand” – is a morbid punchline history delivered to the man who epitomized the Wild West shootist.

- Jesse James: Perhaps no outlaw’s name evokes the Wild West as much as Jesse James. A former Confederate guerrilla, Jesse formed a gang with his brother Frank and spent 15 years robbing banks, stagecoaches, and trains. The press turned the James Gang into Robin Hood figures, claiming Jesse stole from rich Northern banks to give to poor Southern folk. In truth, as historians note, “Jesse James was a ruthless killer who stole only for himself.” He was charismatic but brutal, at times dragging uncooperative bank employees along as human shields or executing captives during robberies. The myth of Jesse James, however, painted him as a dashing highwayman. That myth came crashing down in 1882 in a scene rife with dramatic irony. While straightening a picture on the wall of his own home, Jesse was shot in the back of the head by Bob Ford, a younger gang member whom Jesse trusted. Ford had made a secret deal to betray Jesse for a reward. The assassination was inglorious – no guns blazing duel, just a “dirty little coward” (in the words of a folk song) shooting an outlaw in cold blood. Jesse’s death marked the end of an era: the old breed of banditry extinguished by treachery. Crowds attended Jesse James’s funeral, and his tombstone defiantly branded Robert Ford a traitor. Meanwhile, Bob Ford himself would be reviled and eventually shot to death a decade later. In the tale of Jesse James, we see how legend (the gentleman bandit) and reality (the thief murdered for bounty) often collide tragically.

- Judge Roy Bean: Not all Wild West figures carried guns – some carried gavels, of a sort. In a ramshackle saloon in Langtry, Texas, Roy Bean set himself up as the “Law West of the Pecos.” Bean was a saloonkeeper who somehow got himself appointed justice of the peace, and his courtroom was the barroom. His rulings were notoriously eccentric and often humorous. In one oft-told story, a dead man was found with a pistol and $40 in his pocket; Judge Bean pronounced the corpse guilty of carrying a concealed weapon and promptly fined the corpse $40, which conveniently was the exact amount on the body. Bean pocketed the money and considered justice done. On another occasion, Bean staged a mock hanging: when a cheeky young prisoner angered him, Bean theatrically sentenced him to death. With no gallows in town, they put a noose around the man’s neck and threw the rope over a boxcar. At the last moment, as the prisoner trembled and everyone’s eyes turned heavenward in a fake prayer, Bean’s men whispered for the lad to slip the rope off and run. The terrified fellow took off like a rabbit, and Bean and company broke into laughter and went back to the bar for drinks. Such was frontier justice under Judge Roy Bean – part legal proceeding, part practical joke. Despite his bluster (and love for fining people), Bean never actually hanged anyone in his makeshift court. He was, however, enamored with an English actress, Lillie Langtry (whom he never met), even naming his saloon The Jersey Lily in her honor. Roy Bean’s mix of comedy and lawlessness made him a folk hero of sorts – a reminder that not everything in the Wild West was gunfights and desperadoes; sometimes it was just absurd.

- Bass Reeves: The Wild West was not only populated by white cowboys and outlaws; it was diverse, including one of the greatest lawmen of the age, Bass Reeves, a Black deputy U.S. Marshal. Reeves had been born a slave but escaped to freedom and then served over 30 years enforcing the law across the frontier. He became legendary for his cunning and bravery. Reeves arrested more than 3,000 felons (including murderers and thieves), prowling the Indian Territory (Oklahoma) armed with his wits and his six-shooter. He was a master of disguise – he might pose as a tramp or a preacher to infiltrate an outlaw gang – and was said to be “invincible” after numerous close calls where bullets barely missed him. One popular tale recounts how Reeves once rode alone into a camp of desperadoes and used a clever ploy (pretending to have a letter from one outlaw’s mother, then using the moment of distraction to draw his guns) to capture the entire group. His exploits sound like tall tales, yet Reeves was absolutely real. Some have even speculated he was an inspiration for the Lone Ranger character in later fiction. Bass Reeves’s story, though less famous until recent years, adds rich drama to Wild West history – a man who rose from bondage to become the scourge of outlaws, outshooting and outsmarting the worst the frontier had to offer.

- Buffalo Bill & Calamity Jane: Not all colorful characters were either clear-cut heroes or villains. Buffalo Bill Cody started out as a buffalo hunter and Army scout, earning fame for his marksmanship. But Buffalo Bill’s biggest contribution to Wild West lore was as a showman – in 1883, he created “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West,” a traveling extravaganza that reenacted frontier scenes in arenas across America and Europe. Cody’s shows featured real cowboys, fake Indian attacks (often with actual Lakota performers, including Sitting Bull for a season), stagecoach chases, and shooting exhibitions by the likes of sharpshooter Annie Oakley. This show blurred the lines between reality and fantasy, turning living figures into mythic characters even as the true West was fading. It was said that you usually don’t mythologize an era until it’s over, and indeed, Buffalo Bill’s immensely popular spectacle signaled that the Wild West had become a nostalgic act. Audiences loved it. One of the performers was Martha “Calamity Jane” Canary, a hard-drinking frontierswoman who had been a real scout and occasional prostitute in the Black Hills. Calamity Jane was every bit as colorful as her nickname: she dressed in men’s clothes, cursed like a sailor, and spun amazing (often dubious) tales about herself. She claimed to have ridden for the Pony Express and to have saved an Army captain’s life in an Indian fight (supposedly earning her nickname by “calamity” befell anyone who crossed her). Much of Jane’s life is impossible to verify – she was illiterate and her 1896 autobiography was mostly tall tales. What is known is that she had a kind streak beneath the rowdy exterior. During a deadly smallpox epidemic in Deadwood in 1878, Calamity Jane famously nursed the sick back to health when no one else would risk approaching the diseased. She was also a close friend (in her mind, perhaps more) of Wild Bill Hickok. Jane never quite recovered from Hickok’s murder – she was said to have loved him deeply, though by most accounts Hickok saw her more as a comrade than a sweetheart. In her later years, Calamity Jane was a figure of both comedy and tragedy. Audiences at Buffalo Bill’s show or in dime museums would cheer her outrageous stories, even as she slurred her words from drink. By the time she died in 1903, destitute from alcoholism, she had become a caricature of herself. Yet Deadwood honored her wish (or perhaps honored a local joke) by burying Calamity Jane next to Wild Bill Hickok in the town cemetery – forever pairing their names in legend, if not in life.

Ladies of the Night: "Soiled Doves" of the Wild West

Amid the saloons and gun smoke of the Wild West were the women of the night – the prostitutes and madams euphemistically known as painted ladies, sporting women, or “soiled doves.” They rarely appear in old history textbooks, but these women were an integral part of frontier life. In rough Western boomtowns where men vastly outnumbered women, prostitution flourished openly and was even tacitly accepted as a “necessary service” for lonely miners, cowboys, and soldiers. Some soiled doves operated out of back rooms in saloons or crude shacks called “cribs.” Others worked in more upscale brothels run by savvy madams who could become local business powers in their own right. The life of a prostitute in the Old West could be harsh and dangerous – sexually transmitted diseases were rampant, violence from drunken customers was a constant threat, and many women succumbed to addiction or suicide. Yet a few of these women managed to carve out remarkable, independent lives, marked by courage, humor, and sometimes profound tragedy.

One famous madam was Dora DuFran, the self-proclaimed “Black Hills Queen.” Dora arrived in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, as a teenager during the 1876 gold rush and set up shop as a madam at age 15. Despite her youth, she ran a tight operation, insisting her girls maintain good hygiene and decorum, an oasis of relative cleanliness in a rowdy mining camp. Dora even had a soft spot for pets: after a friend delivered her a batch of kittens, she kept so many cats around that her brothel was jokingly nicknamed the “cathouse,” a term that entered the American lexicon for brothels thereafter. Dora’s most infamous employee was none other than Calamity Jane. Jane, desperate for money, occasionally worked for Dora, but her refusal to bathe and habit of wearing men’s clothes made her unpopular with both customers and Dora. Eventually, Dora relegated Calamity Jane to washing dishes in the kitchen instead – a humorous example of even the Wild West’s toughest gal not quite fitting the role of a genteel lady of the evening! Dora DuFran prospered for decades, running brothels across South Dakota, and died a wealthy woman in the 1930s – living proof that a soiled dove could beat the odds and survive long after the Wild West was tamed. (She’s buried in Deadwood near her friend Calamity Jane, along with a headstone for her beloved pet parrot.)

Not all soiled doves ended their days peacefully, however. Consider the tragic tale of Julia Bulette of Virginia City, Nevada. In the early 1860s, Virginia City was a booming silver mining town, home to the Comstock Lode strike, and was awash with men and money. Julia Bulette was one of the town’s first prostitutes. She was strikingly beautiful by accounts and became something of a local celebrity. Julia was even made an honorary member of the fire brigade for her generosity to the miners – a rare mark of respectability for a prostitute. But in January 1867, Julia’s life met a violent end. She was found murdered in her own bed, beaten and strangled by an unknown assailant. The brutal killing shocked the community. Virginia City’s miners mourned Julia as if she had been a princess. Thousands attended her funeral, and the newspapers eulogized her “beauty” and the kindness she had shown the town’s rough laborers. Her killer turned out to be a drifter who had robbed her; he was caught and hanged publicly the next year – an execution witnessed by none other than writer Mark Twain, who was reporting in Virginia City at the time. Julia Bulette’s story illustrates the two sides of how soiled doves were viewed: she was marginalized as a fallen woman in life, yet after her death, the locals canonized her as the beloved “Queen of the Comstock.” In the Wild West, a person’s legend after death could eclipse the gritty facts of their life.

Frontier prostitutes and madams generated many incredible stories. Mollie Johnson, the “Queen of the Blondes” in Deadwood, ran a rowdy brothel where her girls (many of them blonde, by Mollie’s design) engaged in fierce competition and catfights – sometimes literally brawling in front of customers for dominance. This chaotic sorority provided endless entertainment to the drunken miners. Mollie herself made headlines by marrying a traveling comedian, an African American performer named Lew Spencer – an interracial marriage almost unheard of in 1878. Though the marriage didn’t last, it added to Mollie’s mystique.

Meanwhile, in Colorado, Mattie Silks became one of the West’s wealthiest madams. She was known for her lavish parlor house in Denver and for allegedly engaging in a pistol duel with a rival madam over a lover – a tale that, true or not, titillated the public with the idea of two women fighting for honor with pistols. And then there’s “Big Nose Kate” (Mary Katharine Horony), a prostitute with a fierce devotion to Doc Holliday. When Doc was jailed in Texas on a murder charge, Kate set a building on fire as a distraction and, armed with two six-shooters, helped Doc bust out of jail – a daring escapade that sounds straight out of a dime novel, yet Kate swore it happened. Kate and Doc’s stormy romance and her wild heroics (she was nicknamed “Hellcat Kate” by some) show that soiled doves could be every bit as bold and brash as their gunslinging paramours.

The world of the soiled doves had its own blend of humor, drama, and pathos. These women endured hardships with gumption. Some, like Fannie Porter of San Antonio, ran elegant bordellos and even consorted with famous outlaws (Fannie’s brothel was a favorite hideout of Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch, and she once tricked the pursuing Pinkerton detectives by hiding the outlaws in secret rooms). Others met poetic ends – for instance, Pearl DeVere, a beloved madam in Cripple Creek, Colorado, threw an extravagant party in 1897, overdosed on laudanum that same night, and was sent off with perhaps the fanciest funeral the town ever saw (her coffin lined with roses, a procession of carriages following behind). The soiled doves seldom appear in classic cowboy movies, but their presence in the real West added depth and color to frontier society. They were entrepreneurs, survivors, and sometimes angels of mercy, all dressed in corsets. As one modern historian put it, they were humans too, playing their part in the grand saga of the West.

The Closing of the Frontier

By the early 1890s, the Wild West’s days were numbered. The very forces that had unleashed the frontier boom now brought it to a close. Farms and fences were encroaching on the open range; railroads and telegraph wires knit the far-flung territories closer to civilization; territories became states with more regular law enforcement. A series of pivotal events marked the end of the Wild West era. One was the catastrophic winter of 1886-87, remembered as “The Great Die-Up.” That winter blizzard decimated the gigantic herds of cattle that roamed the plains – up to 90% of the cattle on the open range died in the freezing storms. This disaster financially ruined many free-range ranchers and effectively ended the era of the great cattle drives. In response, surviving ranchers began fencing their lands with the new invention of barbed wire, shifting to enclosed ranches and farming to avoid future losses. The romance of cowboys driving cattle freely across endless prairies faded into history, replaced by a more settled and staid way of ranching after 1887.

Another end-of-an-era moment came in 1890. On December 29, 1890, the U.S. 7th Cavalry clashed with Lakota Sioux Ghost Dancers at Wounded Knee in the Dakota Territory. It was less a battle than a tragic massacre – panicked soldiers killed up to 300 Native Americans, including women and children, effectively crushing the last significant Native resistance on the plains. Wounded Knee is often cited as the sad full stop on the Indian Wars. The frontier, in terms of Indigenous resistance, had been definitively “won” by the U.S., at a horrific cost. Just months later, in early 1891, the U.S. Census Bureau declared that the American frontier, as traditionally understood, no longer existed. Pioneers had settled the West so thoroughly that there was no longer a clear frontier line cutting across the map – the wilderness had been broken into by farms, ranches, towns, and territories. As one historian famously noted, “The frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history”. In essence, the government was acknowledging that the era of westward expansion was over; the Wild West had been tamed.

Some historians and writers pin the end of the Wild West to symbolic dates, such as 1895 or 1900, thirty or so years after it began. By 1895, indeed, many of the iconic characters of the Wild West were gone or had retired from the gunfighting life. “Problems of lawlessness were gradually being sorted out” by the mid-1890s, as one historian notes. The old outlaw gangs had been broken – the Younger brothers were in prison, Jesse James was long dead, Billy the Kid and John Wesley Hardin were buried, Wyatt Earp had moved to California, and even the Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy were about to flee to South America by the end of the ’90s. In 1895, the crack-shot sheriff Pat Garrett (who killed Billy the Kid) was himself shot dead, and John Wesley Hardin was murdered in El Paso – violent postscripts to the bloody chapter of frontier violence. These events were noted in the papers, but they felt like the last echoes of a waning age. The vigilante justice and range wars of earlier decades, such as the Lincoln County War of 1878 or the Johnson County War of 1892, had largely given way to courts and established jurisdiction as territories became states. Oklahoma Territory was opened to homesteaders during the famous land rushes of 1889 and the 1890s, clearing out the outlaw havens in “Indian Territory.” By 1900, the U.S. had 45 states, and places like Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona were soon to follow, bringing formal law with them.

In truth, the end of the Wild West was more a whimper than a bang. One could say it ended when the last buffalo herds were slaughtered and fenced off from the plains, or when the last stagecoach was replaced by a railroad, or when the Model T automobile first puttered down a dusty western trail. The frontier didn’t die on a single day; it transitioned gradually into modernity. But symbolically, Americans of the time knew it was over. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show had already transformed the West into entertainment by the 1890s, packaging cowboy duels and Indian attacks into a romantic circus for the world to see. You don’t turn your history into a show unless you sense that history is safely in the past. By the turn of the century, writers and old lawmen alike were penning memoirs, trying to capture the vanishing world of their youth, often embellishing it to meet the public’s insatiable appetite for Western lore.

The Wild West era, although brief (only about 30 years), left a lasting legacy on American culture. It was a time of extreme characters and conflicts, of humor and horror, of freedom and lawlessness colliding. Legendary events like the O.K. Corral shootout or Custer’s Last Stand became foundational myths, even as real people lived and died in those dusty battles. Colorful figures from Wyatt Earp to Calamity Jane took on lives of their own in dime novels and in the national psyche. And the soiled doves and card sharks and homesteaders – all the everyday folk of the frontier – contributed their threads to the grand tapestry of the West. When the frontier closed, America didn’t simply move on; it began to mythologize. From early Western pulp novels to Hollywood films and modern TV series, the Wild West has been reimagined countless times, usually with more romance than reality. But behind every legend was a real story – usually messier, sometimes funnier or sadder, and always human.

In the narrative of the Wild West, the lines between fact and fiction often blur, yet that’s precisely what makes it such a rich story. As the frontier lawman-turned-showman Bat Masterson supposedly said in his later years, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” The Wild West is the era where many legends became accepted as fact. Yet by doing the deep research, as we have here, we can appreciate the true complexity of those times – the grit and greed, the courage and folly. It was an era born in the aftermath of one war and ended on the eve of modern America, only thirty years, but packed with tales that still enthrall us today. The Wild West lives on in our collective imagination as a place of endless horizon and endless possibility – a place where outlaws and heroes, cowboys and Native Americans, soiled doves and showmen all dance through history in a rough-and-tumble, poignant American epic.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME:

Abraham Lincoln

President During United States Civil War

Portrait Created by Cyberlink's Subscription Power Director 365 AI Image Generator

Jesse James

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Deadwood, SD, 1876

1876 is the year Wild Bill Hickok was murdered in Deadwood & the year he, Calamity Jane, and entourage rode into Deadwood.

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Wild Bill Hickok

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Cowboy Singing, Painting by Thomas Eakins

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Doc Holliday

Not Quite 21 Years of Age

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Billy the Kid

1879 or 1880

Shot to Death, 1881

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Robert (Bob) Ford,

Posing With the Firearm He Reportedly Used to Murder Jesse James

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Lillie Langtry

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Martha Jane Canary,

a.k.a.

"Calamity Jane"

Image Via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Dora DuFran

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Mark Twain

Photo by A.F. Bradley in His Studio

This image is available in the Print and Photo Division of the Library of Congress under the digital code cph.a08820.

Restoration and colorization:

Courtesy of CaesarDynamics.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, and no changes were made to the image.

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Creative Commons License

Mattie Silks

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

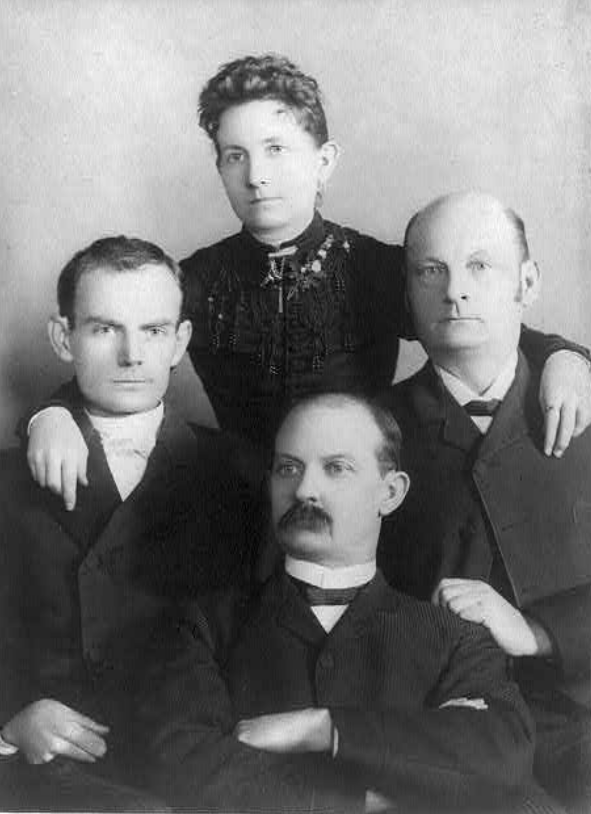

The Younger Siblings

Henrietta (top) with (left to right) Robert, Cole, and James. Brother John Is Not Pictured.

Image Via Wikimedia Commons,

Public Domain

Add comment

Comments